Estimated Reading Time: 35 minutes

Executive Summary

Greenberg (2002) defines employee theft as “the unauthorized taking, control, or transfer of money and/or property or time theft of the formal work organization that is perpetrated by the employee during the course of occupational activity.” Bamfield (2006) states that employee theft, the largest contributor to inventory shrinkage, has been less thoroughly examined compared to shoplifting. However, the issue of internal theft and its impact on organizations has recently garnered the attention of many retailers (Reagan, 2023), including the leading UK retailer Sainsbury’s PLC. The purpose of This report is to develop a comprehensive strategic marketing solution to address the pressing issue of internal theft at Sainsbury’s PLC.

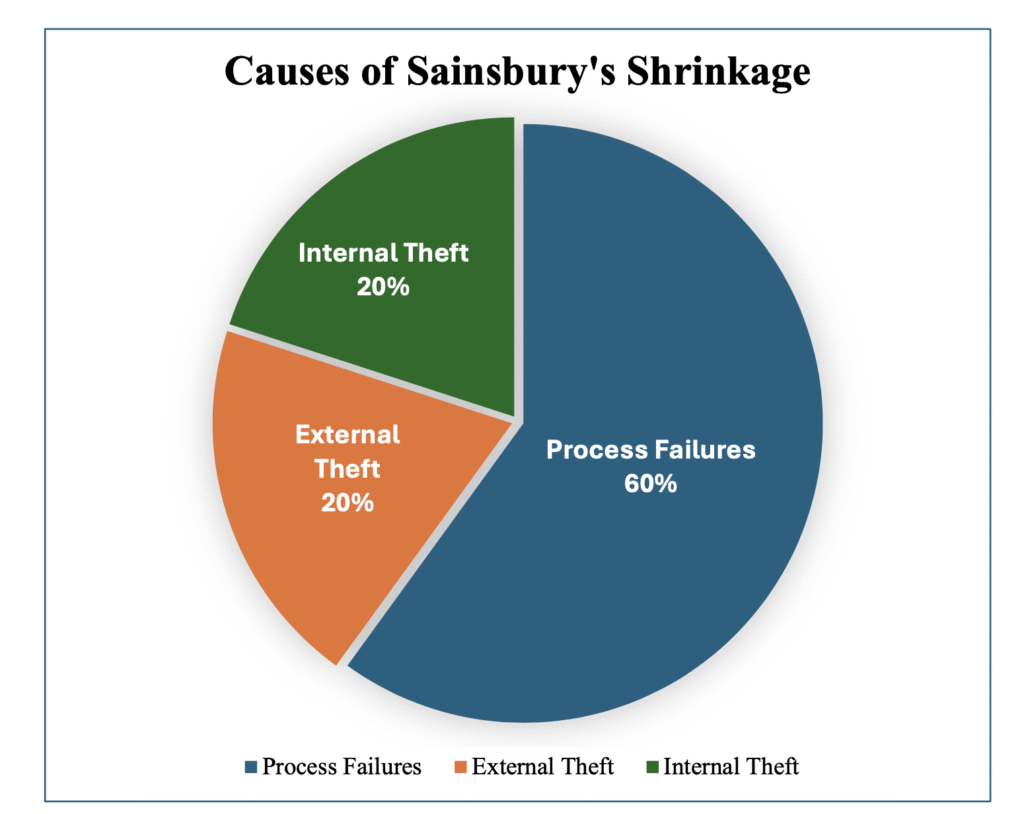

Through a detailed Situational Analysis, the report outlines key external factors influencing internal theft using PESTLE analysis, including economic pressures exacerbated by Brexit and rising inflation, as well as the impact of job satisfaction and criminal behaviours toward retail staff. These factors have contributed to a rise in workplace theft, as employees experience increased financial strain and dissatisfaction. Internally, Sainsbury’s faces significant process failures and organizational culture issues that create an environment conducive to the elements of the theft triangle, increasing the likelihood of theft. Notably, internal theft accounts for 20% of the company’s shrinkage, equalling the losses caused by external theft.

This report identifies three strategic Marketing Objectives based on the SMART framework and Hierarchy of Effects Theory:

- Increase employee awareness of internal theft and its consequences, with a goal of raising awareness levels by 80% through structured educational programs and ongoing assessments.

- Cultivate a collaborative workplace culture that promotes mutual supervision and accountability, utilizing team-based reward systems grounded in Social Norms Theory to foster ethical behavior.

- Enhance whistleblowing mechanisms by encouraging extraordinary ethical behaviours like proactive reporting of theft through secure, anonymous channels, with the aim of reducing internal theft by 50%.

This report outlines three Strategic Pillars:

- Building Awareness of Internal Theft: Implementing a comprehensive training program to educate employees on the various forms of internal theft and the serious impact these behaviors have on the company’s financial health and job security. This initiative is reinforced through surveys, quizzes, and visual aids designed to track progress and raise awareness.

- Fostering Collaboration and Mutual Supervision: Introducing a team-based reward system to encourage employees to monitor and support each other in preventing theft. This strategy leverages social norms to create an environment where honesty and ethical behavior are valued and rewarded.

- Strengthening Whistleblowing Systems: Enhancing existing whistleblowing processes to ensure anonymity and incentivizing the reporting of theft through tangible rewards such as financial incentives and paid leave. This initiative is crucial in encouraging employees to actively engage in maintaining a theft-free environment.

A VRIO Analysis of the proposed strategies confirms their value to the organization, while acknowledging the potential challenges of imitation and implementation. Sainsbury’s is well-positioned to implement these strategies due to its established internal communication channels and organizational resources. However, successful execution will require consistent management and oversight across the company’s numerous stores to ensure alignment and effectiveness.

Aligned with Sainsbury’s vision to ‘be the most trusted retailer where people love to work and shop’ and its purpose ‘driven by our passion for food, together we serve and help every customer,’ the proposed strategies prioritize the development of a more transparent, ethical, and accountable organizational culture. This approach is supported by a robust internal communication plan designed to deliver key messages through accessible channels.

2. Introduction

According to BBC News (2024), the internal theft crime rate has been rising significantly over the past few years, causing problems for many retailers. “While the traditional primary needs have been related to accommodation, substance use, mental health, and attitudes, thinking, and behaviors, we have recently observed an increase in finance, benefits, and debt as presenting needs,” said Dafydd Llywelyn, Police and Crime Commissioner. “We are unable to attribute this to any single underlying factor.”

Sainsbury’s is an established retail company with over 1,400 stores and 148,000 employees in the UK, which suffers from severe internal theft losses each year. The purpose of this report is to address the issue of internal theft at Sainsbury’s by identifying a comprehensive solution, utilising various analytical tools and relevant theories.

A significant portion of the information in this report is sourced from an internal theft meeting (2024) with James McAlister, Loss Prevention Change Manager at Sainsbury’s PLC, as well as from observations and experiences during a visit to Sainsbury’s Fosse Park store.

3. Situational Analysis

Based on the market share of retailers in Great Britain (Kantar Worldpanel, 2024), Sainsbury’s main competitors in the retail industry are Tesco, Aldi, and Asda. The following section of the report will include a PESTLE analysis of the retail industry, with an organisational analysis of Sainsbury’s embedded, focusing on factors that may impact internal marketing and internal theft.

3.1. Political

A report published by the Centre for European Reform (2022) emphasizes the negative effects of Brexit on the UK’s GDP, investment, and trade. While there is debate regarding Brexit’s impact on the UK’s high inflation rate, it has been associated with rising food prices. Other than that, The Russian invasion of Ukraine is disrupting the global food supply, especially sunflower oil, wheat, and corn. The reduction in raw materials for human and animal consumption could lead to higher dairy and meat prices, placing further pressure on consumer’s spending (Global Data, 2022).

New data released by Cifas (2023) indicates that employee theft has increased by 19% as the rising cost of living fuels a surge in workplace crime (Zurich, 2023). This may increase the likelihood of employees stealing to meet their own financial needs. Senior Specialty Lines claims expert, Rose Sutton, stated: “As the cost-of-living pressures intensify, employee theft has risen sharply, suggesting that some workers may be resorting to desperate measures to make ends meet” (Zurich, 2023).

3.2. Economic:

Transported Asset Protection Association (2023) states that employees working in warehouses, distribution centres, and stores contribute to 40% of retail theft losses, amounting to £3.2 billion. Company’s salary, employee welfare, environment and corporate culture are no doubt some of the most crucial factors that impact employee’s attitude, motivation and loyalty to the organization (Lee and Liu, 2021). Moreover, previous research (Hollinger and Clark, 1983) has shown that job dissatisfaction is an important factor contributing to employee theft. Employees typically compare their company with other companies in the same industry, negative perception can lead to distrust of the company, a lack of a sense of value, and behaviours that violates company policies (Greenberg and Barling, 1996).

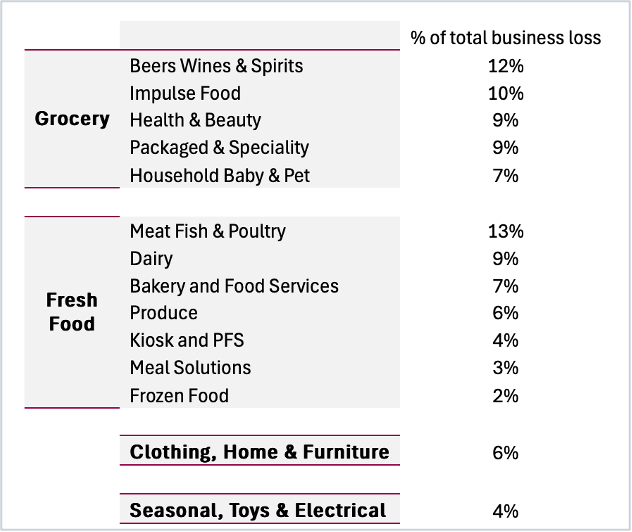

According to Indeed (2024), Sainsbury’s average salary of warehouse workers is distinctly lower than that of its competitors in the industry (Figure 1). With similar duties but lower pay, employees may perceive the company as petty and unappreciative of their contributions. Rising inflation further exacerbated employee dissatisfaction (Lage and Greer, 1981), employee might perceive that despite the substantial profits earned, the company is indifferent to their financial difficulties (Louis, 2011). This disconnect could potentially result in a crisis of dishonest behaviours like stealing within the organization (Greenberg, 1990). According to Sainsbury’s PLC (2024), it is estimated that approximately 60% of Sainsbury’s shrinkage results from process failures (Figure 2).

These failures occur when procedures in the physical flow of goods are not properly followed, leading to errors and inefficiencies (Berman and Evans, 2018). This is significantly higher than the 27% average for retail process failures (Beck and Chapman, 2003). Compared to the average retailer’s external theft and internal theft, Sainsbury’s internal theft is severer than the average retailers as well. Of the remaining 40% losses, half (20%) is attributed to internal theft, while the other half (20%) is due to external theft. This indicates that Sainsbury’s internal theft issues are just as significant as external theft problems. A report by ECR Retail Loss (2003) suggests that European retailers could boost their average profits by 29% if they managed to reduce their shrinkage losses by half. The substantial financial losses resulting from these failures and thefts may be influencing stakeholder perception and diminishing their willingness to invest.

3.3. Social:

3.3.1. Retail Worker

Organizational culture plays a big role in relation to employee behaviours like internal theft (Lee and Liu, 2021). The key elements include working environment (Ashkanasy et al., 2014), employee engagement (Kahn, 1990), organisational values and ethics (Treviño and Nelson, 2016), social and peer influence (Cialdini and Goldstein, 2004) and diversity and inclusion (Roberson, 2006). However, there are certain characteristics and inherent traits of the retail job market that make changing or fostering a positive working culture challenging. Firstly, retail companies tend to have a relatively high proportion of part-time employees, as part-time positions can more easily accommodate peak periods of store operations due to their flexibility (UK Parliament, 1998).

Research by Rousseau (1995) and Shore and Tetrick (1994) found that part-time employees may perceive their relationship with the organization as more short-term and economically driven, whilst full-time employees typically demonstrate higher levels of commitment to their organizations, driven by a sense of obligation and the perceived sacrifices involved in leaving, both in terms of relationships and practical benefits (Gakovic and Tetrick, 2003).

For many part-time employees, job in retail primarily serves as a means to earn essential income to support their livelihood. Without the intention of pursuing a long-term career in the field, they may be less motivated to engage in efforts that improve the organizational environment or contribute to the company’s sustained development. Moreover, retail warehouse and stockroom workers are classified as blue-collar, these jobs tend to be more standardized and repetitive, offering limited opportunities for both professional and personal growth within the workplace (Eriksson, 2011).

According to Herzberg’s motivation-hygiene theory (1959), factors like achievement, the work itself, responsibility, advancement and personal growth are crucial motivators to job satisfaction. A survey by Breakroom (2024) reveals that approximately 70% of Sainsbury’s employees reported not having opportunities to improve their skills, learn new abilities or take on additional responsibilities in their roles. Therefore, Sainsbury’s employees might exhibit lower motivation and commitment at work, as their job satisfaction—which can affect internal theft—does not meet the intrinsic factors necessary to fulfil the needs of self-actualisation (Herzberg, 1966).

With that being said, a study by Hennequin (2007) suggests that for blue-collar workers, factors such as teamwork, social recognition, and work-life balance hold greater importance than traditional metrics like promotions and salary. Even without advancement opportunities, these workers can still experience a sense of success through fulfilment in their roles. Hence, changing the nature of retail jobs to ‘increase job satisfaction’ might be highly challenging and unrealistic; however, the company can work on ‘reducing job dissatisfaction’ by addressing hygiene factors such as interpersonal relations, company policies, administration, supervision, and working conditions (Herzberg et al., 1959). Since employees are more likely to engage in criminal behaviours as they become increasingly dissatisfied with their jobs, they may potentially resort to internal theft either to meet their own needs or as a form of retaliation against their employer (Wells, 2001).

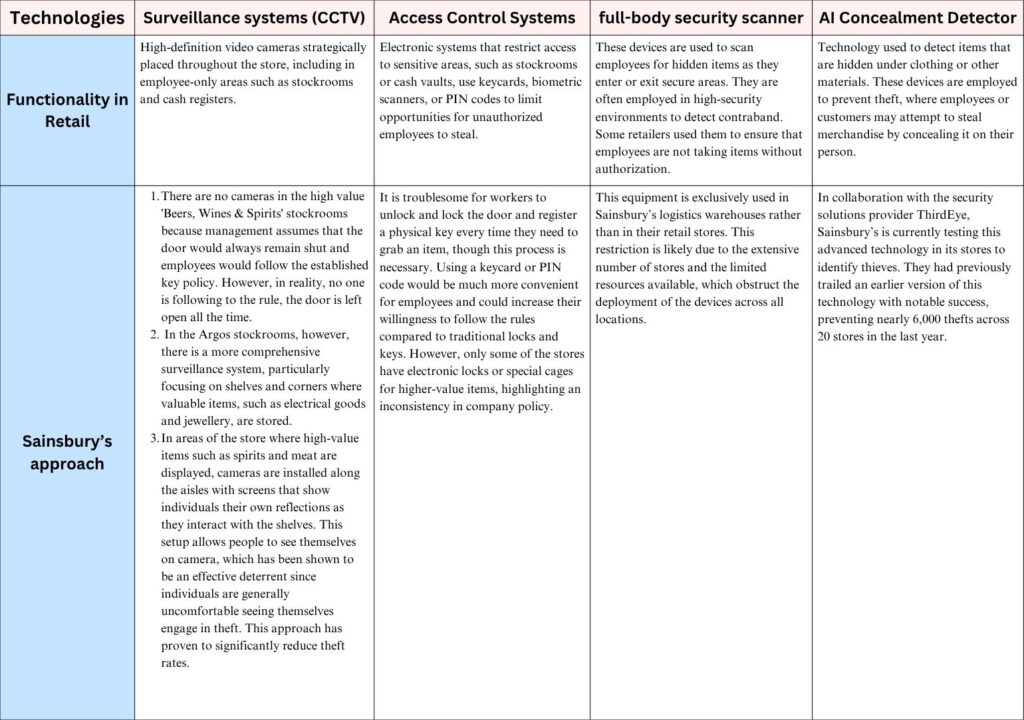

Proper employee training, maintaining an organized environment, and ensuring effective communication with staff are among the most important factors in preventing employee theft (Cutherell, 2024). The table below provides an analysis of Sainsbury’s performance regarding these factors.

3.3.2. Inventory Safety:

- Figure 3 illustrates the categories of internal theft by percentage. The data shows that ‘Beers, Wines & Spirits’ experiences the highest theft rate, making it the category most in need of attention. Despite this, there is no CCTV in the storeroom because management assumes that the door will remain shut and employees will adhere to the key policy. In reality, the rule is not properly enforced. The door is consistently left open while the individual on duty is not held accountable for failing to comply with company policy. This creates security loopholes and increases the risk of inventory theft, as anyone can access the stockroom without permission at any time.

- In the delivery area, truck keys are supposed to be secured in a lockbox on the wall, with drivers required to request access. However, much like the rules in the wine storeroom, this procedure is frequently disregarded. Additionally, the warehouse doors are always left open, posing a significant security risk (Figure 4).

- The route from the loading area to the Argos stockroom is notably long and contains several dead zones, exposing a significant risk of theft.

3.3.3. Body Search

- Employees are chosen randomly for a search either at the door entrance or while at work. To avoid bias, a random button is used: an employee is searched only if the button lights up red when pressed.

- In the Argos stockroom where valuable items like digital goods and jewelries are stored, a specialized digital device monitors and records the number of theft checks conducted across all stores. Each store is required to perform 28 searches per week. With a total of 70 employees, this means each employee has about a one-in-three chance of being searched weekly.

- Due to the randomness of the selection process and the insufficient number of searches, the current system does not fully guarantee security. Management has proposed increasing the number of searches to further reduce the risk of theft, highlighting ongoing concerns about loss prevention and the effectiveness of current security measures.

3.3.4. Management Inconsistency

- The HR team should conduct a thorough employee credibility check during the hiring process. However, some employees have reported instances where individuals who were previously dismissed have been rehired after six months. This suggests that there may be issues with the organization’s hiring standards and policies.

- Consuming food and beverages in the warehouse are prohibited. Employees are permitted to eat and drink only in the canteen, where the company provides free food and personal belongings storage lockers. However, we observed someone drinking in one of the storerooms, which indicates poor management and a lack of discipline within the company.

As stated above, it is evident that Sainsbury’s demonstrates several inconsistencies and vulnerabilities in managing employee conduct and warehouse security. These issues could potentially cause employees to underestimate the seriousness of non-compliance.

3.4. Technological

3.5. Legal

A survey by the British Retail Consortium (2023) revealed a 50% increase in violence and abuse against retail staff in the year leading up to September 2023. On average, 1,300 incidents of violence or verbal abuse occurred daily, with around 8,800 resulting in injury. These incidents ranged from racial abuse and sexual harassment to physical assaults and threats with weapons. This situation should be taken seriously to avoid greater internal theft as it can severely affect the hygiene factors that reduce employee satisfaction. The Protection of Workers Act (Scottish Parliament, 2021) came into force in Scotland in 2011, making it a specific offence to assault, threaten, or abuse a retail worker. However, retail unions and industry bodies have called for the legislation to be extended across the rest of the UK to ensure all shop staff are protected from abuse (Webber, 2021).

In July 2024, the government introduced amendments to the Crime and Policing Bill aimed at protecting vulnerable shop staff. These amendments include new legislation that establishes a specific offence for assaulting a shopworker. This development has received widespread approval from the retail sector (Radojev, 2024). Mo Razzaq, the national president of the Federation of Independent Retailers, said: “What we need now is real action to curb the overwhelming tide of crime against retailers and their staff. Everyone deserves to feel safe at work and to have their businesses protected from criminals” (O’Riordan, 2024).

Additionally, the National Retail Crime Steering Group, co-chaired by the British Retail Consortium (BRC) and Kit Malthouse MP, the Home Office Minister for Crime and Policing, brings together retailers, government officials, police, and trade associations, focusing on collaborating to combat retail crime, particularly incidents of violence against shop workers (Wynn, 2022). From the retailer’s perspective, these new laws and approaches are expected to improve workplace hygiene factors and increase employee satisfaction to help prevent the exacerbation of internal theft.

| Retailer | Average Salary per Hour |

| Aldi | £13.69 |

| Tesco | £13.16 |

| Asda | £13.13 |

| Sainsbury’s | £10.97 |

4. Marketing Objectives

As stated in the situation analysis section, the severity of internal theft at Sainsbury’s can be attributed to the organizational environment meeting the three essential elements of the fraud triangle: perceived pressure, perceived opportunity, and rationalisation (Albrecht et al., 2006). This marketing solution will apply the Hierarchy of Effects Theory (Colley, 1961) to three SMART objectives (Doran, 1981) successively in order to develop a marketing plan aimed at addressing Sainsbury’s internal theft issue.

4.1. SMART 1:

S: Raise employees’ awareness of internal theft and its seriousness.

M: Increase 80% of employees’ awareness.

A: Using surveys and tests to ensure employees’ understanding.

R: Employees frequently underestimate the seriousness of internal theft, perceiving company property as part of their work environment and assuming it can be used freely. For example, pencils or photocopies are often seen as perks of the job. Many employees also rationalise their stealing behaviours by believing that the company is large enough to absorb small losses (Gross-Schaefer et al., 2000), without realizing that this mindset could lead to significant financial burdens for the company and may even impact its survival. This suggests that employees’ understanding and awareness of internal theft are inadequate and inappropriate.

T: within a year.

4.2. SMART 2:

S: Use team-based reward systems and emphasising company welfare to enhance friendly mutual supervision among employees.

M: Using surveys and monthly team performance to assess success.

A: Group employees by store units, utilising social norm theory to foster a collaborative and mutually beneficial work environment.

R: Rewards function as motivational tools with positive reinforcement to shape desired employee behaviours (Chiang and Birtch, 2012) and reduce unethical workplace conduct (Shoaib and Baruch, 2019).

T: within a year.

4.3. SMART 3:

S: Reduce internal theft rate by half.

M: Using surveys and monthly team performance to assess success.

A: Research by Dewi et al. (2020) found that (1) Individuals are more likely to engage in whistleblowing when their identity is protected, (2) they are more inclined to blow the whistle when a financial reward is offered, and (3) the combination of identity protection and financial incentives significantly increases their intention to report wrongdoing.

R: ncourage employees to actively engage in fostering an anti-theft attitude with team reward and company welfare.

T: within a year.

By implementing these SMART goals effectively, the company aims to cultivate a culture where employees are aware of the importance of protecting company resources, actively involved in reducing theft and promote ethical behaviours in the workplace.

5. Strategy

5.1. Sainsbury’s Corporate Strategy

5.1.1. Mission Statement

“Make good food joyful, accessible and affordable for everyone, every day.”

5.1.2. Vision

“Be the most trusted retailer where people love to work and shop.”

5.1.3. Purpose

“Driven by our passion for food, together we serve and help every customer.”

5.2. Internal STP

Although Sainsbury’s was unable to provide exact figures, the chart below presents the estimated composition of its workforce (McAlister, 2024):

| Demographic | Group | Percentage |

| Age | 16-24 | 35% |

| 25-64 | 65% | |

| Gender | Women | 60% |

| Men | 40% | |

| Employment | Part-time | 65% |

| Full-time | 35% |

Bipp (2010) discovered that factors such as gender and age could affect certain job crafting behaviour, such as seeking additional structural and social resources. At Sainsbury’s, the percentage of female employees and those in the older age group is about one-third higher compared to their male and younger colleagues. Older employees tend to focus more on tasks that safeguard their self-concept and offer opportunities for positive events. Additionally, both older workers and women exhibit a greater preference for autonomy and feedback (Bipp, 2010). These are the critical aspects that our marketing plan should prioritize.

For part-time employees who exhibit lower motivation to engage in activities that enhance the organizational environment and male employees that seek less additional social resources, implementing a reward system could serve as a tangible incentive. According to Chiang and Birtch (2012), organizational rewards help businesses effectively align employee behaviours with strategic objectives by making employees feel valued for their contributions (Njanja et al., 2013).

5.3. Procedure Justice

Research by Shapiro et al. (1995) identified that the primary factors influencing employee theft are perceptions of procedural justice and employees’ assessments of the appropriateness of theft. Procedure justice refers to the fairness of the processes and decision-making criteria used in organizational procedures (Lemons and Jones, 2001). It encompasses employees’ perceptions of how changes, such as theft reduction programs, are implemented and whether they feel their views are considered. High levels of procedural justice are associated with greater employee support for management actions, even if those actions are unfavourable (Brockner, 2002).

Examples of procedural justice include providing employees with a ‘voice’ in the decision-making process, ensuring that changes related to theft reduction are communicated clearly, and offering explanations for the reasons behind the loss prevention program. Furthermore, incorporating educational components into interventions and empowering employees with the authority and responsibility for theft detection are critical elements that contribute to their positive perceptions of the fairness of these procedures (Shapiro et al., 1995).

5.4. Strategy 1: Internal Theft Awareness Building

5.4.1. Internal communication and channels

As stated earlier, employees’ understanding and awareness of internal theft are insufficient, with many unaware of the severity of the damage caused to the organization. A study by Shapiro et al. (1995) suggests that enhancing employees’ understanding of theft can help reduce such behaviours. Additionally, Hollinger and Clark (1983) found that both the certainty and severity of organizational deterrent were linked to incidents of employee theft. When employees are aware that irresponsible conduct will inevitably result in detection and severe disciplinary action, they are less likely to engage in such behaviours. To further combat employee theft, it is essential for Sainsbury’s to inform its employees that internal theft is a serious issue that must be addressed.

According to Tench and Yeomans (2009), internal communication refers to the deliberate use of communication strategies to systematically shape the knowledge, attitudes, and behaviours of existing employees. In order to deliver clear and accurate information to employees, proper internal communication is needed (FitzPatrick and Valskov, 2014). Research by Jackson (2003) examining employees’ responses to incoming communications found that 70% opened the application to read messages within six seconds, and 85% did so within two minutes of receipt.

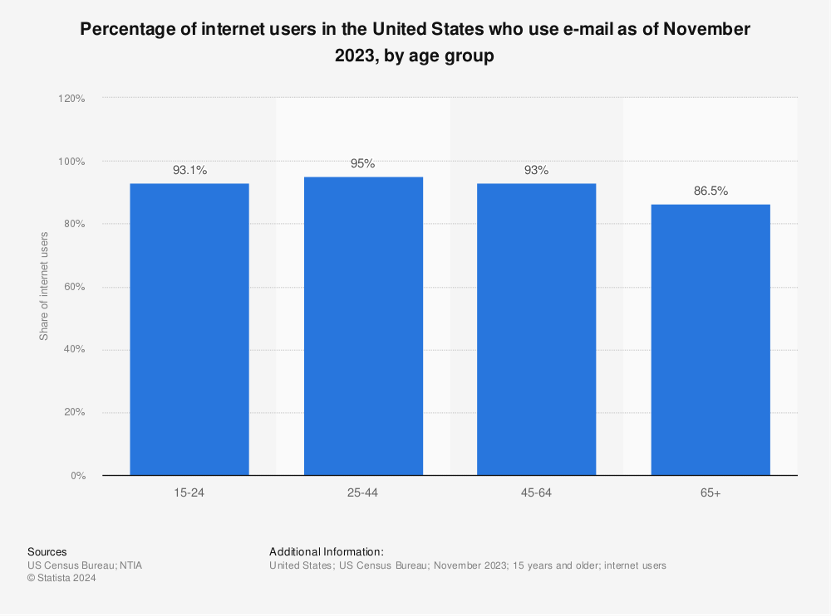

Moreover, unlike other channels such as social media platforms, email usage shows no significant variation across age groups. Figure 5 illustrates that the penetration rate of email remains consistently high across all age demographics, with minimal differences. Therefore, leveraging the company’s email bulletins to disseminate information about the seriousness of internal theft is essential. Regular updates and informative pieces can help employees understand how internal theft affects the company’s bottom line and how it might affect their job security.

5.4.2. Education and Training Programme:

This plan seeks to Launch organized education and training program that educate employees about the various forms of internal theft and their implications. These sessions can be tailored to different job positions to highlight the negative effects of such behaviours, not only on the company but also on their team and job stability.

Ethics training is recognized as a key approach to enhancing employees’ ethical decision-making and behaviours (Valentine and Fleischman, 2004). It is entirely logical for companies to prioritize the task of institutionalizing ethics within their organizations (Graham, 2009). A core ethical code in business must clearly communicate to all employees that any misconduct, whether by an employee, officer, or executive, that violates applicable laws, regulations, or basic tenets of business ethics will result in immediate disciplinary action (Gross-Schaefer, 2000). Programs and policies must be designed to promote the widespread adoption of such normative guidance across the organization (Adams et al., 2001). Company must clearly communicate its standards and ensure their effective distribution throughout the organizational structure (Palmer and Zakhem, 2001).

5.4.3. Surveys and Quizzes:

One of the most effective ways to detect fraud and identify internal control weaknesses is simply by asking about it (Hansen et al., 2000). Create a series of surveys and quizzes to measure employees’ initial awareness levels regarding internal theft. After the education and training program, follow up with assessments and surveys to measure improvements in awareness levels. To meet the goal of an 80% increase in awareness, the surveys will be a critical tool in understanding the success of the educational initiatives. Establishing feedback mechanisms to encourage employees to share their perspectives on the knowledge and training they receive is essential, as our primary employee demographic values autonomy and feedback in the workplace. Understanding their perceptions of the educational materials will help the company refine its approach and ensure that the information is well-received and understood. Establish forums or anonymous feedback channels where employees can ask questions or express concerns about the internal theft policy. This helps clarify ambiguities and further raises awareness.

5.5. Strategy 2: Collaborative Workplace and

5.5. Strategy 2: Collaborative Workplace and

5.5. Strategy 2: Collaborative Workplace and Mutual supervision

5.5.1. Social Norms and Routine Behaviours

Internal theft often thrives in environments where employees feel detached from the company or its goals. When employees do not perceive themselves as stakeholders in the company’s success, they may be more inclined to engage in unethical behaviours, including theft (Gakovic and Tetrick, 2003). Implementing team-based reward systems can leverage Social Norms Theory (Perkins and Berkowitz, 1986), which suggests that individuals are influenced by the behaviours of those around them.

Therefore, employees are more likely to act ethically when they know their peers are also inclined to act in the company’s best interests. We can shape employees’ anti-theft attitudes into routine behaviours that align with moral standards and prevailing workplace ethics (Bhattacharya et al., 2023). By doing so, acceptance is achieved when group norms are internalized, leading to conformity both publicly and privately (Sowden et al., 2018).

This strategy aims to use social norms interventions to provide accurate information about peer group norms, with the goal of correcting misperceptions of these norms. Team-based reward system and mutual supervision within teams can foster a culture where employees hold each other accountable, creating a collaborative environment where employees are motivated to work together to prevent theft and share in their collective successes.

5.5.2. Develop Team-Based Rewards:

Reward structures within organizations include both financial and non-financial incentives, which may be fixed or contingent upon the performance of individuals, groups, or the organization as a whole (Milkovich and Newman, 2008). Design a reward system where store units or teams are rewarded for achieving certain performance metrics, including low rates of internal theft. These rewards could include bonuses, additional paid time off, or team-building activities that emphasize group collaboration and loyalty to the company.

5.5.3. Encourage Mutual Supervision:

Evaluate team performance and reward the well performed team to reinforce the positive social norms and create a collaborative workspace. Working in pairs is also known to decrease incidents of employee theft (Gregory, 2013). By designing team-based and collaborative work environments, employees will feel more connected to their peers and less inclined to engage in theft. Visibility and teamwork can deter individuals from taking advantage of company resources when they know their actions are visible to their coworkers.

5.5.4. Emphasize Company Welfare:

According to Men and Stacks (2014), the Employee-Organization Relationship refers to the extent of mutual trust between an organization and its employees, agreement on who has the authority to influence, satisfaction with each other, and commitment to one another. To engage employees and encourage their cooperation with the strategy, it is crucial to ensure they are aware of the company’s commitment to welfare. This awareness helps improve their perception of the hygiene factors that contribute to job dissatisfaction. Regular communication should emphasize that reducing internal theft allows the company to invest more in employee welfare, including enhanced benefits, higher wages, and increased job security.

5.6. Strategy 3: Whistleblowing and Proactive Behaviour

5.6.1. Whistleblowing

Encouraging employees to take an active role in maintaining an anti-theft culture through whistleblowing is critical to reducing theft incidents. However, research by Near and Miceli (1986) found that the whistle blowers were more likely to suffer retaliation if they lacked the support of their supervisors and managers. Gross-Schaefer et al. (2000) indicates that many employees within a company genuinely want to address theft issues but lack the necessary support from the organization. Many employees are hesitant to report theft behaviours, either because they feel it will harm their relationships with colleagues or because they believe the company will not take adequate steps to address the issue.

By improving the marketing strategies surrounding the whistleblowing system and offering tangible rewards for those who report theft incidents, employees will feel empowered to come forward with valuable information and showcase extraordinary ethical behaviours (Bhattacharya, C.B. et al. 2023). In last stage of the marketing plan, enhancing the system to make whistleblowing a positive, rewarded behaviours is key to deterring theft.

5.6.1. Promote Whistleblowing:

- Confidential Reporting Systems: Ensure that whistleblowers can report incidents of internal theft anonymously. Create secure, online reporting systems where employees can submit information without fear of retaliation.

- Regular Communications: Remind employees regularly of the existence of the whistleblowing system and its importance. Encourage transparency and reinforce the notion that reporting theft benefits everyone within the company.

- Educate employees about the benefits of whistleblowing: Launch internal marketing campaigns that explain how whistleblowing protects the entire workforce. Communicate that whistleblowing helps reduce theft, allowing the company to put more efforts on employee welfare.

5.6.3. Offer Rewards for Whistleblowers:

Create a reward system where employees who report legitimate theft cases are rewarded with financial incentives or additional paid time off. This can act as a powerful motivator, particularly for employees who may be hesitant to report internal theft. Recognise whistleblowers who contribute to lowering theft incidents in a non-public but meaningful way, such as private meetings with upper management or anonymous bonuses.

5.7. VRIO

This report will utilize the VRIO framework (Barney, 1991) to evaluate the marketing strategy, assessing four dimensions: value, rarity, imitability, and organization of resources and capabilities.

5.7.1. Value

- Internal Theft Awareness Building: The plan emphasizes improving employee understanding and awareness of internal theft. This is valuable as it directly impacts the reduction of theft, enhances ethical behavior, and aligns with the organizational goal of reducing losses and maintaining trust.

- Collaborative Workplace and Mutual Supervision: Fostering a collaborative environment and leveraging social norms to reduce theft adds value by creating a stronger, more accountable workforce. This strategy supports teamwork and mutual supervision, which can lead to reduced theft and increased overall performance.

- Whistleblowing and Proactive Behavior: Promoting whistleblowing and offering rewards for reporting theft adds value by providing a mechanism to detect and address theft. Ensuring anonymity and rewarding whistleblowers encourage more reporting, which can significantly reduce theft and reinforce a culture of transparency.

5.7.2. Rarity

- Internal Theft Awareness Building: Many companies have recently begun to pay more attention to the issue of shrinkage. However, few are actively designing and implementing educational training programs to address employee awareness of internal theft.

- Collaborative Workplace and Mutual Supervision: Using team-based rewards and mutual supervision to combat theft is somewhat rare. Many organizations do not integrate these social norms and reward-based strategies as deeply into their theft prevention plans.

- Whistleblowing and Proactive Behavior: A well-structured whistleblowing system with rewards is relatively rare, particularly when combined with comprehensive education and secure reporting channels. Many companies have whistleblowing policies, but the integration of tangible rewards and regular communication is less common.

5.7.3. Imitability

- Internal Theft Awareness Building: The approach of using internal communication channels and targeted educational programs can be imitated by other organizations.

- Collaborative Workplace and Mutual Supervision: This approach might be imitated, but successfully implementing and maintaining a culture of mutual supervision and collaborative rewards requires ongoing commitment and can be difficult to sustain effectively.

- Whistleblowing and Proactive Behavior: The concept of rewarding whistleblowers is imitable, but establishing a trusted, anonymous system with effective communication and meaningful rewards can be challenging. The success of this strategy depends on the organization’s culture and the effectiveness of its implementation.

5.7.4. Organisation

- Internal Theft Awareness Building: Sainsbury’s appears to have the organizational capability to implement this strategy through its established internal communication channels and training programs. Ensuring effective execution will depend on how well these channels are utilized and integrated into daily operations.

- Collaborative Workplace and Mutual Supervision: Sainsbury’s is a well-established company, recognized as the third-largest food retailer in the UK. While Sainsbury’s extensive resources should ensure that these systems are well-organized, secure, and trusted by employees, the complexity of managing a large-scale operation with diverse workplace cultures across various stores may lead to inconsistencies and operational challenges that hinder overall success.

- Whistleblowing and Proactive Behavior: The success of the whistleblowing strategy depends on the implementation of secure reporting systems and the ability to offer and manage rewards. Implementing systems to evaluate performance and manage rewards will require careful oversight and flexible adjustability.

5.7.5. Summary

- Value: The strategies (theft awareness, collaborative work environment, whistleblowing) provide significant value by reducing theft, enhancing accountability, and promoting ethical behavior, aligning with Sainsbury’s goals.

- Rarity: The use of comprehensive training for theft awareness, team-based supervision, and a whistleblowing system with rewards is relatively rare compared to most competitors.

- Imitability: While the strategies are imitable, successfully replicating them requires sustained commitment, particularly in fostering a culture of collaboration and trust around whistleblowing and supervision.

- Organization: Sainsbury’s has the organizational infrastructure to implement these strategies, but effective execution depends on consistent management across diverse stores.

Overall, the plan leverages valuable and somewhat rare strategies to address internal theft and is organized to support successful implementation.

Figure 5: Percentage of internet users in the United States who use e-mail as of November 2023, by age group (Ceci, 2024).

6. Tactics

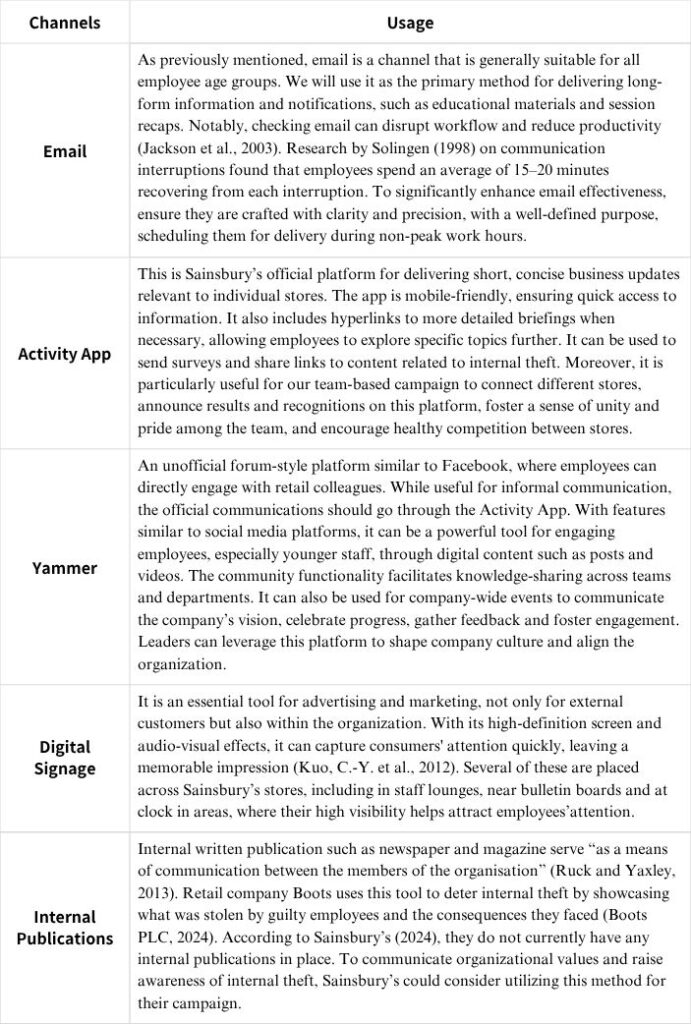

6.1. Internal communication and channels

The table below outlines the channels Sainsbury’s can use to effectively communicate with its employees:

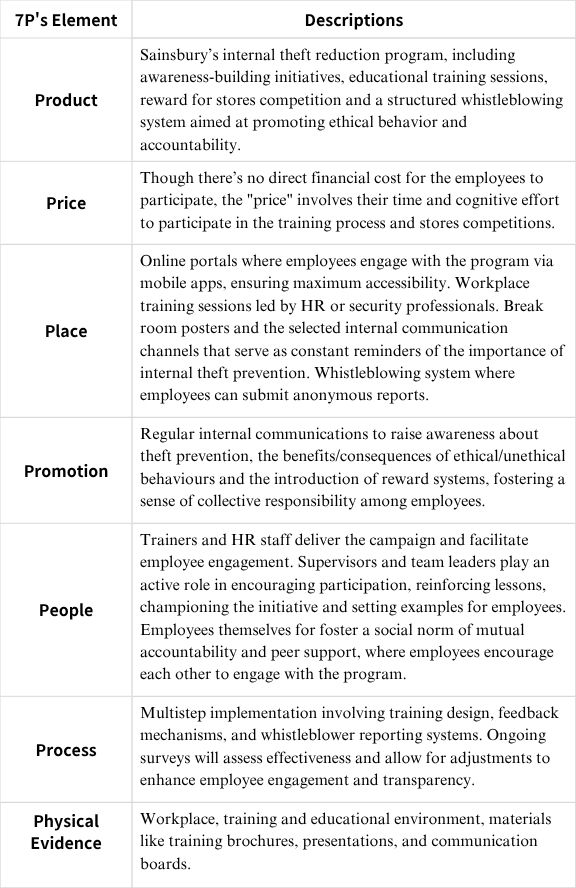

6.2. Internal Marketing Mix

6.3. Tactic for Strategy 1: Internal Theft Awareness Building

6.3.1. Education and Training Programme:

There are loopholes in Sainsbury’s current ethical training programme. While mandatory training on ‘colleague safety’ is provided, shrink and theft prevention are only addressed through optional video content rather than official and mandatory channels. Despite the availability of tools such as security tags and reporting systems, relying on informal communication and current practices is insufficient. James McAlister, the Loss Prevention Change Manager at Sainsbury’s said: “My view is we could do more with official training.” Implementing formal, mandatory training on shrink and theft prevention would create a more consistent and effective approach, ensuring that all employees are well-informed and aligned with best practices.

6.3.2. Surveys and Quizzes:

The surveys should include Pre-Campaign Surveys and Post-Campaign Feedback Mechanisms. Investigate current awareness levels through anonymous surveys and quizzes. Design multiple choice questions that focus on the severity and damage of internal theft and highlight the benefits and consequences of ethical/unethical behaviours:

- Question: Did you know how much money organizations lose each year due to internal shrinkage?

Purpose: Raise awareness by highlighting the significant financial losses caused by internal theft. - Question: Which costs organizations more: external theft or internal theft?

Purpose: Highlight that both external and internal theft cause same levels of financial loss (20%), which may surprise many employees. - Question: How do employees benefit from the reduction of internal theft?

Purpose: Emphasize the advantages employees can gain by supporting the company’s anti-theft initiatives and fostering a culture of honesty. - Question: What happens if employees are caught stealing company property?

Purpose: Deter theft by emphasizing the severe consequence of dismissal for such actions.

After training, conduct follow-up assessments to track improvements in awareness and evaluate the program’s effectiveness. Offer anonymous channels for employees to ask questions about theft policies, as our target demographics (women and older employees) tend to prefer autonomy and feedback at workplace. Gamify the quizzing process to increase engagement. These quizzes should test employees’ knowledge of theft prevention, reinforce the material and offer small rewards (e.g., goods) for successful completion.

6.3.3. Visual Aids:

Place posters and flyers in highly visible areas such as clock-in/out points, noticeboards, changing rooms, restrooms, and high-risk stock areas, featuring catchphrases like ‘Did You Know Employee Theft Threatens Your Job Stability?’ Highlight the potential harm that internal theft causes to employees and the organization. Emphasize the costs (loss-framed) of normalizing a culture of theft, as research shows that people are more sensitive to the pain of loss than the pleasure of gain (Tversky & Kahneman, 1981). We can also utilize the digital signage and bulletin boards in the staff lounges, where free Sainsbury’s food and drinks are available to employees. Display content that reminds staff they don’t need to steal, as the company is always providing and welcoming them to enjoy free items in the lounges.

6.4. Tactics for Strategy 2: Collaborative Workplace and Mutual supervision

6.4.1. Team-Based Reward System and Mutual Supervision:

Employees will be grouped according to store units to effectively integrate anti-theft attitudes into routine behaviours (Bhattacharya, C.B. et al. 2023) within the organisation. To ensure fairness, stores will compete with others of similar scale and staff numbers, with geographical location also taken into account.

Team performance will be evaluated monthly, using metrics such as internal theft incidents and inventory discrepancies. Teams that demonstrate lower theft rates a higher level of collaboration will be rewarded with incentives like bonuses, additional paid time off, or team-building activities that emphasize teamwork and loyalty to the company. Information, progress updates, results and celebrations will continue to be communicated through the previously mentioned channels.

With the previous awareness-building sessions and ethical training combined with the team-based reward system, employees will develop a new understanding: internal theft is an unethical behaviour that harms not only the company but also themselves and their colleagues. Employees will recognize that by not participating in theft and working towards shared goals, they can earn respect and rewards alongside their hardworking peers. When everyone is aligned with the same objective, there is a greater chance of successfully shaping anti-theft social norms (Perkins and Berkowitz, 1986) within the organization.

This alignment may also increase the sense of guilt among potential offenders, as they may feel pressured to contribute to the team’s success or, at the very least, avoid being the ‘black sheep’ by engaging in unethical behaviours. Additionally, the company should offer not only tangible rewards but also public recognition across communication channels, reinforcing these positive norms and fostering a collaborative work environment.

6.4.2. Visual Aids:

Place posters at the similar areas mentioned in the first strategy.

The posters feature:

- Title: “Get Rewarded for Your Honesty!”

Refer to the team-base competition.

- Subtitle: “Your Honesty is More Valuable Than Goods!”

Refer to employees can get reward by not selling their kindness, as the campaign function with the fact that they could win additional benefits at work above board rather than Use deception as a means.

- Content: Provide clear guidance on the team-based competitions, outlining the criteria for evaluating excellent performance and the types of rewards available.

- Visual Communication: In the image, there are two figures representing employees. One has a heart made up of store items like alcohol, meat, and vegetables, with a prohibition symbol over it, symbolizing the unwanted unethical behavior. The other person has a normal heart emitting a bright yellow glow, representing the happiness and rewards brought by good virtues.

This poster uses orange, a colour often associated with health and vitality as its main colour. In design, orange is typically seen as approachable and welcoming (Chapman, 2021). The design incorporates the colours of Sainsbury’s logo, linking honest behaviours to the organization’s core value of being ‘the most trusted retailer where people love to work’. It employs both emotional and rational marketing appeals by prioritizing the value of employees’ honesty over material goods and highlighting the rational benefits of aligning with the organizational objectives. To capture attention and generate interest, the poster emphasizes key information. Detailed operational content will be communicated through the selected channels.

6.5. Tactics for Strategy 3: Whistleblowing and Proactive Behavior

The final stage of our marketing solution aims not only to instil non-stealing as a routine behaviour among employees but also to cultivate extraordinary ethical behaviours that exceed basic moral standards (Bhattacharya, C.B. et al. 2023).

6.5.1. Existing System

Sainsbury’s existing whistleblowing system has several issues that need to be addressed:

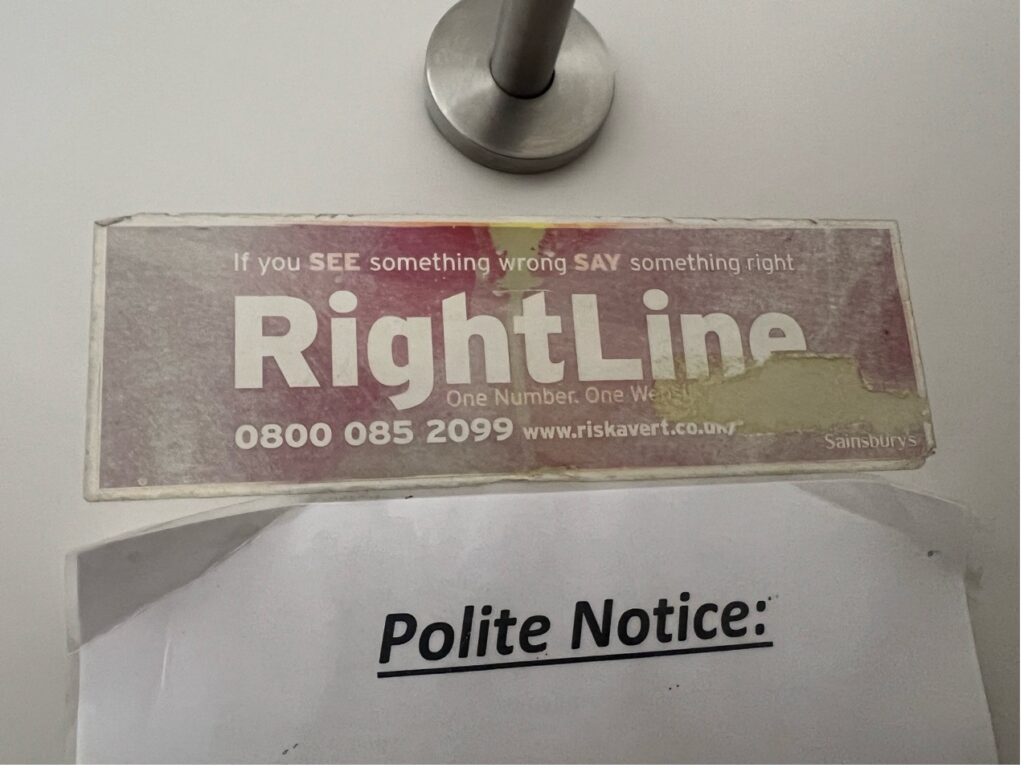

- Outdated Materials: There are no posters, only small signs that are over 30 years old and are now faded and outdated (see Figure 6).

- Lack of Visual Appeal: The materials consist mostly of text with no images, making them neither eye-catching nor intuitive.

- Insufficient Incentives: The system does not offer adequate incentives for reporting, leading people to avoid involvement and focus on their own tasks.

- Reduced Visibility: Due to the reasons above, the original posters have become virtually invisible in the environment, with employees growing accustomed to them and eventually forgetting they exist.

6.5.2. Encourage Report behaviours

- Extraordinary Ethical Behaviors: Through prior awareness initiatives and team-based competitions, employees are likely to cultivate a sense of justice and mutual oversight, encouraging them to engage in extraordinary ethical behaviors.

- Anonymous Reporting Platforms: Promote a secure online system for the confidential reporting of theft incidents through internal communication channels.

- Awareness Campaigns: Utilize training and education programs to inform employees that whistleblowing is essential for the company’s success, emphasizing that reporting theft helps protect their jobs and strengthens the team.

- Support from Managers: Train managers to handle whistleblowing reports with sensitivity and support. Establish a feedback loop to inform whistleblowers about how their reports were addressed, while maintaining confidentiality.

6.5.3. Rewards for Whistleblowers

- Tangible Incentives: Provide cash bonuses, gift cards, or paid time off for legitimate theft reports, ensuring the anonymity of the individuals involved.

- Private Recognition: Implement private recognition opportunities, such as exclusive meetings with senior management or access to career advancement programs.

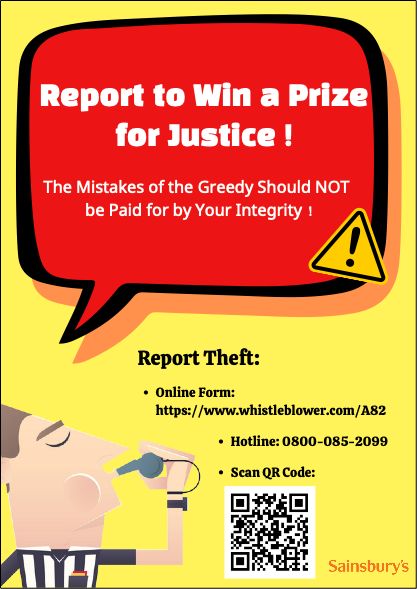

6.5.4. Visual Aids:

The posters should be placed in discreet locations, such as restrooms and changing rooms, to ensure the anonymity of whistleblowers.

The posters feature:

- Title: “Report to Win a Prize for Justice!”

Refer to employees that developed extraordinary ethical behaviours and create incentives.

- Subtitle: “The mistakes of the greedy should not be paid for by your integrity”

Transform the mindset of threatening employees due to distrust into one that prioritizes employee benefits.

- Call to Action: Directlyprovide report methods on the poster.

Hotline/Online form/QR code.

- Visual Communication: A whistleblower is depicted in side profile, with the sound of the whistle represented in a dialogue box conveying the message. This imagery symbolizes zero tolerance for unethical behavior and the courage to speak up.

This poster design incorporates the colours red, symbolizing importance, and yellow, associated with danger (Chapman, 2021). The yellow background serves as a warning sign to grab attention, while the red dialogue box emphasizes key messages. Red, known to elevate blood pressure and respiration (Chapman,2021), may encourage employees to take action in reporting issues. This poster employs fear and emotional marketing appeals. Fear is depicted through the whistleblower’s concern that their rights may be violated, while employees who engage in theft fear being caught. Emotional appeals evoke a sense of justice and integrity, encouraging employees to take pride in ethical behaviours. The imagery of the whistleblower symbolizes bravery and the importance of standing up against wrongdoing.

7. Conclusions & Recommendations

In conclusion, the proposed marketing solution for Sainsbury’s aims to effectively combat internal theft by fostering a culture of honesty, mutual supervision, and proactive behaviours among employees. By implementing formal training programs, enhancing communication channels, and establishing a robust whistleblowing system with tangible rewards, Sainsbury’s can significantly reduce theft incidents and promote ethical conduct.

However, considering the scale of Sainsbury’s stores and the number of staff, maintaining consistency and effective management across the entire plan may be a huge significant challenge. Company should regularly assess the effectiveness of these initiatives through employee feedback and performance metrics, ensuring continuous improvement and alignment with organizational goals. By prioritizing employee engagement and create unity mutual supervision teams, Sainsbury’s can create a more secure and trustworthy work environment, ultimately benefiting both the organization and its workforce.

8. References

Adams, J. S. et al. (2001) ‘Codes of ethics as signals for ethical behaviours’, Journal of Business ethics, 29, pp. 199-211. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026576421399 (Accessed: 15 September 2024).

Albrecht, W.S. et al. (2006) ‘The ethics development model applied to declining ethics in accounting’, Australian Accounting Review, 16(38), pp.30-40. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1835-2561.2006.tb00323.x (Accessed: 15 September 2024).

Ashkanasy, N. M. et al. (2014) ‘Understanding the physical environment of work and employee behavior: An affective events perspective’, Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(8), pp. 1169-1184. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1973 (Accessed: 5 September 2024).

Barney, J. (1991) ‘Firm Resources and Sustained Competitive Advantage’, Journal of Management, 17(1), pp. 99-120. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108 (Accessed: 17 September 2024).

Brockner, J. (2002) ‘Making Sense of Procedural Fairness: How High Procedural Fairness Can Reduce or Heighten the Influence of Outcome Favourability’, The Academy of Management Review, 27(1), pp. 58–76. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/4134369 (Accessed: 18 September 2024).

Beck, A. and Chapman, P. (2003) A Proven Approach to Shrinkage Reduction. ECR Retail Loss. Available at: https://www.ecrloss.com/research/shrinkage-and-stock-loss-in-supply-chain (Accessed: 8 August 2024).

Bailey, A.A. (2006) ‘Retail employee theft: a theory of planned behavior perspective’, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 34(11), pp. 802-816. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/09590550610710219 (Accessed: 5 September 2024).

Bamfield, J. (2006) ‘Sed quis custodiet? Employee theft in UK retailing’, International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 34(11), pp. 845-859. Available at: 10.1108/09590550610710246 (Accessed: 19 September 2024).

Bipp, T. (2010) ‘What do People Want from their Jobs? The Big Five, core self‐evaluations and work motivation’, International journal of selection and assessment, 18(1), pp. 28-39. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2389.2010.00486.x (Accessed: 16 September 2024).

Berman, B. R. and Evans, J. R. (2018) Retail Management: A Strategic Approach. 13th edn. London: Pearson.

Bhattacharya, C. B. et al. (2023) ‘Corporate purpose and employee sustainability behaviours’, Journal of Business Ethics, 183(4), pp. 963-981. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-022-05090-5 (Accessed: 18 September)

British Retail Consortium (2023) Retail Crime a “Crisis That Demands Action”. British Retail Consortium. Available at: https://brc.org.uk/news/corporate-affairs/retail-crime-a-crisis-that-demands-action/ (Accessed: 9 September)

Breakroom (2024) Sainsbury’s. Breakroom. Available at: https://www.breakroom.cc/en-gb/employers/Sainsburys (Accessed: 6 September 2024).

Boots PLC (2024) Internal Theft Meeting Minutes. Unpublished internal company document.

Colley, R. H. (1961) Defining advertising goals for measured advertising results. New York: Association of National Advertisers

Cialdini, R. B. and Goldstein, N. J. (2004) ‘Social influence: Compliance and conformity’, Annu. Rev. Psychol, 55(1), pp. 591-621. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.142015 (Accessed: 3 September 2024).

Chiang, F. F. T. and Birtch, T. A. (2011) ‘The Performance Implications of Financial and Non‐financial Rewards: An Asian Nordic Comparison’, Journal of Management Studies, 49(3), pp. 538-570. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2011.01018.x (Accessed: 13 September 2024).

Chiang, F. F. and Birtch, T. A. (2012) ‘The performance implications of financial and non‐financial rewards: An Asian Nordic comparison’, Journal of Management Studies, 49(3), pp. 538-570. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2011.01018.x (Accessed: 17 September 2024).

Verlet, J.R.R. (2021) GroupVerlet. Available at: http://www.verlet.net/ (Accessed: 14 May 2021).

Chapman, C. (2021) Color Theory for Designers, Part 1: The Meaning of Color. Available at: https://www.smashingmagazine.com/2010/01/color-theory-for-designers-part-1-the-meaning-of-color/ (Accessed: 20 September 2024).

Cifas (2023) ‘Employers Urged to Prioritise Internal Security as Cases of Employee Theft Rise by Nearly Three-quarters’, Cifas, 31 October. Available at: https://www.cifas.org.uk/newsroom/insiderthreatfraudscape23 (Accessed: 3 September 2024).

Cutherell, D. (2024) How Employee Theft Works and How to Prevent It. Prosegur. Available at: https://www.prosegur.co.uk/newsdetails/blog/how-employee-theft-works-and-how-to-prevent-it-uk# (Accessed: 14 September 2024).

Ceci, L. (2024) Percentage of internet users in the United States who use e-mail as of November 2023, by age group. Statista. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/271501/us-email-usage-reach-by-age/ (Accessed: 17 September 2024).

Doran, G. T. (1981). ‘There’s a S.M.A.R.T. Way to Write Management’s Goals and Objectives’, Management Review, 70, pp. 35-36. Available at: https://community.mis.temple.edu/mis0855002fall2015/files/2015/10/S.M.A.R.T-Way-Management-Review.pdf (Accessed: 13 September 2024).

Dewi, N. A. et al. (2020) ‘The effect of identity protection and financial reward on Whistleblowing intention in public sector organization: Experimental study’, International Conference on Tourism, Economics, Accounting, Management And Social Science, pp. 37-49. Available at: (Accessed: 19 September 2024).

Eriksson, Y. U. (2011) Commitment to Work and Job Satisfaction. New York: Routledge.

FitzPatrick, L., & Valskov, K. (2014). Internal communications: a manual for practitioners. London: Kogan Page Publishers.

Greenberg, J. (1990) ‘Employee theft as a reaction to underpayment inequity: The hidden cost of pay cuts’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 75(5), pp. 561–568. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.75.5.561 (Accessed: 30 August 2024).

Greenberg, L. and Barling, J. (1996) ‘Employee theft’, Trends in organizational behaviours, 3, pp. 49-64. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/employee-theft/docview/228915407/se-2 (Accessed: 3 September 2024).

Greenberg, J. (2002) ‘Who stole the money and return? Individual and situational determinants of employee theft’, 89(1), pp. 985-1004. Available at: 10.1108/09590550610710246 (Accessed: 19 September 2024).

Gross-Schaefer, A. et al. (2000) ‘Ethics Education in the Workplace: An Effective Tool to Combat Employee Theft’, Journal of Business Ethics, 26(2), pp. 89–100. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25074331 (Accessed: 13 September 2024).

Gakovic, A. and Tetrick, L.E. (2003) ‘Perceived organizational support and work status: A comparison of part-time and full-time employees’, Journal of Organisational Behavior, 24(5), pp. 649-666. Available at: 10.1002/job.206. (Accessed: 3 September 2024).

Graham, M. L. (2009) Business ethics: An Analysis of a Company’s Training Program Influence on Employee Behaviours and Morale. California: Pepperdine University.

Gregory, J. G. (2013) 6 Tips to Reduce Employee Theft. Entrepreneur. Available at: http://www.entrepreneur.com/article/229816 (Accessed: 14 May 2021).

Global Data (2022) Impact of the Russia-Ukraine Conflict on Retail Industry – Thematic Research. Global Data. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/employee-theft/docview/228915407/se-2 (Accessed: 5 September 2024).

Herzberg, F. I. et al. (1959) The motivation to work. 2nd edn. New York: John Wiley.

Herzberg, F. (1966) Work and the Nature of Man. Cleveland: World Pub.

Hollinger, R. C. and Clark, J. P. (1983) Theft by employees. Lexington: Lexington Books.

Hollinger, R. C. and Clark, J. P. (1983) ‘Deterrence in the workplace: Perceived certainty, perceived severity, and employee theft’, Social forces, 62(2), pp. 398-418. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/62.2.398 (Accessed: 1 September 2024).

Hennequin, E. (2007) ‘What “career success” means to blue‐collar workers’, Career development international, 12(6), pp. 565-581. Available at: https://www.emerald.com/insight/content/doi/10.1108/13620430710822029/full/html (Accessed: 6 September 2024).

Hansen, S. D. et al. (2011) ‘Corporate social responsibility and the benefits of employee trust: A cross-disciplinary perspective’, Journal of business ethics, 102, pp. 29-45. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0903-0 (Accessed: 16 September 2024).

Idnani, S. (2024) ‘People Stealing to Feed Family, Says Police Commissioner’, BBC News, 9 February. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-wales-politics-68240168 (Accessed: 11 September 2024).

Indeed (2024) Warehouse Worker Hourly Salaries in the United Kingdom. Available at: https://uk.indeed.com/ (Accessed: 30 August 2024).

Jackson, T. et al. (2003) ‘Reducing the effect of email interruptions on employees’, international journal of Information management, 23(1), pp. 55-65. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0268-4012(02)00068-3 (Accessed: 16 September 2024).

Jackson, T. et al. (2003) ‘Understanding email interaction increases organizational productivity’, Communications of the ACM, 46(8), pp. 80–84. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/859670.859673 (Accessed: 17 September 2024).

Kahn, W. A. (1990) ‘Psychological Conditions of Personal Engagement and Disengagement at Work’, The Academy of Management Journal, 33(4), pp. 692–724. Available at: https://doi.org/10.2307/256287 (Accessed: 1 September 2024).

Kuo, C.-Y. et al. (2012) ‘A Study on the Effectiveness of Digital Signage Advertisement’, International Symposium on Computer, Consumer and Control, pp. 169-172. Available at: 10.1109/IS3C.2012.51. (Accessed: 17 September 2024).

Kantar Worldpanel (2024) Market share of grocery stores in Great Britain from January. Statista. Statista Inc. Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/280208/grocery-market-share-in-the-united-kingdom-uk/ (Accessed: 30 August 2024).

Lage, G.M. and Greer, C.R. (1981) ‘Adjusting Salaries for the Effects of Inflation’, Review of Business and Economic Research, 16(3), p. 1. Available at: https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/adjusting-salaries-effects-inflation/docview/1295950602/se-2?accountid=12152 (Accessed: 29 August 2024).

Lemons, M. A. and Jones, C. A. (2001) ‘Procedural justice in promotion decisions: using perceptions of fairness to build employee commitment’, Journal of managerial Psychology, 16(4), pp. 268-281. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940110391517 (Accessed: 17 September 2024).

Louis, H. (2011) ‘Salary Adjustments and Inflation’, University of the Third Mil, 1(35), p. 35. Available at: https://www.ndu.edu.lb/Library/Files/Spirit/english53.pdf#page=34 (Accessed: 27 August 2024).

Lee, Y. and Liu, W. (2021) ‘The Moderating Effects of Employee Benefits and Job Burnout among the Employee Loyalty, Corporate Culture and Employee Turnover’, Universal journal of management, 9, pp. 62-69. Available at: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/The-Moderating-Effects-of-Employee-Benefits-and-Job-Lee-Liu/10c55ec2b76b49c001369988ce624025185d808e?utm_source=direct_link (Accessed: 30 August 2024).

Milkovich, G.T. and Newman, J.M. (2008) Compensation. 9th edn. USA: McGraw Hill.

McAlister, J. (2024) Email to I-Chen Ho, 19 August.

McAlister, J. a (2024) Email to I-Chen Ho, 9 September.

Near, J. P. and Miceli, M. P. (1986) ‘Retaliation against whistle blowers: Predictors and effects’, Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(1), pp. 137–145. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.1.137. (Accessed: 17 September 2024).

Njanja, L. et al. (2013) ‘Effect of reward on employee performance: A case of Kenya Power and Lighting Company Ltd., Nakuru, Kenya.’, International Journal of Business and Management, 8(21), pp. 41-49. Available at: 10.5539/ijbm.v8n21p41 (Accessed: 17 September 2024).

O’Riordan, L. (2024) ‘Retailers praise tougher shoplifting and assault laws in amended Crime and Policing Bill’, Drinks Retailing, 18 July. Available at: https://drinksretailingnews.co.uk/retailers-praise-tougher-shoplifting-and-assault-laws-in-amended-crime-and-policing-bill/ (Accessed: 8 September 2024).

Perkins, H. W. and Berkowitz, A. D. (1986) ‘Perceiving the community norms of alcohol use among students: Some research implications for campus alcohol education programming’, International Journal of the Addictions, 21(9-10), pp. 961–976. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3109/10826088609077249 (Accessed: 18 September 2024).

Palmer, D. E. and Zakhem, A. (2001) ‘Bridging the gap between theory and practice: Using the 1991 federal sentencing guidelines as a paradigm for ethics training’, Journal of Business Ethics, 29(1-2), pp. 77 – 84. Available at: 10.1023/a:1006471731947 (Accessed: 16 September 2024).

Rousseau, D. M. (1995) Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Roberson, Q. M. (2006). ‘Disentangling the Meanings of Diversity and Inclusion in Organizations’, Group and Organization Management, 31(2), pp. 212-236. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601104273064 (Accessed: 1 September 2024).

Ruck, K. and Yaxley, H. (2013) ‘Tracking the rise and rise of internal communication from the 1980s’, The Proceedings of the International History of Public Relations Conference. Available at: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Heather-Yaxley-2/publication/275657118_Tracking_the_rise_and_rise_of_internal_communication_from_the_1980s/links/5543a3b00cf24107d39632de/Tracking-the-rise-and-rise-of-internal-communication-from-the-1980s.pdf (Accessed: 17 September 2024).

Reagan, C. (2023) Retail theft isn’t actually increasing much, major industry study finds.

Radojev, H. (2024) ‘The King’s Speech sets out action on retail crime, HFSS and work reforms for the new government’, Retail Week, 17 July. Available at: https://www.retail-week.com/people/the-kings-speech-has-set-out-action-on-retail-crime-hfss-and-workplace-rights/7046657.article (Accessed: 9 September 2024).

Shore, L. M. and Tetrick, L. E. (1994) ‘The psychological contract as an explanatory framework in the employment relationship’, Trends in organizational Behavior, 1, pp. 91-109. Available at: https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1994-98115-007 (Accessed: 8 September 2024).

Shapiro, D. L. et al. (1995) ‘Correlates of employee theft: A multi‐dimensional justice perspective’, International Journal of Conflict Management, 6(4), pp. 404-414. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1108/eb022772 (Accessed: 29 August 2024).

Solingen, et al. (1998) ‘Interrupts: just a minute never is’, IEEE Software, 15(5), pp. 97-103. Available at: 10.1109/52.714843. (Accessed: 18 September 2024).

Scottish Parliament. (2011) Protection of Workers (Retail and Age-restricted Goods and Services) (Scotland) Act 2021. Legislation.gov.uk. Available at: https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2021/6/contents (Accessed: 9 September 2024).

Sowden, S. et al. (2018) ‘Quantifying compliance and acceptance through public and private social conformity’, Consciousness and Cognition, 65, pp. 359-367. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2018.08.009. (Accessed: 5 September 2024).

Shoaib, S. and Baruch, Y. (2019) ‘Deviant Behaviours in a Moderated-mediation Framework of Incentives, Organizational Justice Perception, and Reward Expectancy’, Journal of business ethics, 157, pp. 617-633. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3651-y (Accessed: 14 September 2024).

Springford, J. (2022) The cost of Brexit to June 2022. Centre for European Reform. Available at: https://www.cer.eu/insights/cost-brexit-june-2022 (Accessed: 3 September 2024).

Sainsbury’s PLC (2024) Internal Theft Meeting Minutes 2.8.24. Unpublished internal company document.

Tench, R. and Yeomans, L. (2009) Exploring Public Relations. 2nd edn. Pearson Education Inc.

Treviño, L. K. and Nelson, K. A. (2016) Managing Business Ethics: Straight Talk About How to Do It Right. 5th edn. Oxford: Wiley.

Transported Asset Protection Association (2023) Retail Risk – New Report Highlights £7.9 Billion of Losses in 2023 from UK Warehouses, Distribution Centres and Stores. Transported Asset Protection Association. Available at: https://tapaemea.org/news/retail-risk-new-report-highlights-7-9-billion-of-losses-in-2023-from-uk-warehouses-distribution-centres-and-stores/ (Accessed: 28 August 2024).

UK Parliament (1998) Select Committee on Education and Employment Appendices to the Minutes of Evidence: Memorandum from J Sainsbury plc. UK Parliament. Available at: https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm199899/cmselect/cmeduemp/346/346ap49.htm (Accessed: 8 September 2024).

Valentine, S. and Fleischman, G. (2004) ‘Ethics Training and Businesspersons’ Perceptions of Organizational Ethics’, Journal of Business Ethics, 52(4), pp. 391-390. Available at: 10.1007/s10551-004-5591-6 (Accessed: 17 September 2024).

Wells, J. T. (2001) ‘Why employees commit fraud’, Journal of Accountancy, 191(2), pp. 89-91. Available at: https://www.journalofaccountancy.com/issues/2001/feb/whyemployeescommitfraud.html (Accessed: 16 September 2024).

Wynn, G. (2022) ‘NRCSG against shop worker abuse and violence – practical solutions and resources’, British Retail Consortium. 18 July. Available at: https://brc.org.uk/news/operations/nrcsg-against-shop-worker-abuse-and-violence-practical-solutions-and-resources/ (Accessed: 11 September 2024).

Zurich (2023) ‘Employee theft jumps by a fifth as cost of living pressures mount’, Zurich, 23 February. Available at: https://www.zurich.co.uk/news-and-insight/employee-theft-jumps-by-a-fifth-as-cost-of-living-pressures-mount (Accessed: 3 September 2024).